By Rob Assise, Homewood-Flossmoor High School

In the prelude to this article, I provided a story that hopefully caused readers to evaluate their programs and think about what transfers from practice to competition. During my very first class at Millikin University in 1999, Dr. William Keagle told my class, “Question everything.” Since I was 17 at the time and already knew everything, it did not have much of an impact on me, but it is now a centerpiece of how I view the world. This article will provide training-specific concepts to consider from elite coaches. The information provided is a snapshot of a snapshot of these coaches’ work and my interpretation of it. I encourage you to “question everything” in terms of how the concepts transfer to your specific situation.

Before I proceed, I think it is important to set up some parameters for the information presented.

- The focus will be addressing methods that develop speed.

- Although it may be favored to how it applies to track and field, any sport that involves movement can benefit.

- I probably seemed anti-squat based on the preceding article. I’m not. The majority of our athletes did a traditional squat last season an average of once per week. I have heard from many sources that ideal strength to body weight ratio in the squat is 2:1 and between 2:1 and 3:1 for the deadlift. These are probably solid guidelines to follow for most because it gives an indicator of whether the athlete is “strong enough.”

I often think of training high school athletes from the perspective of an alteration of the Pareto Principle (the 80-20 rule). If I run a relatively “traditional” program to develop speed, hopefully 80% of my athletes will achieve optimal progress. The other 20% may progress, but not optimally. What I am looking for is optimal progress for everyone! My search of transfer is an investigation to develop options to be used in our program’s “phone booth” so all athletes who enter exit as the super version of themselves. The work of these men have challenged my beliefs and improved the contents of my phone booth.

The Alternative Methods of Frans Bosch

There may not be a more polarizing figure in the world of physical preparation than Frans Bosch. There seems to be very little middle ground when his ideas are discussed: People either love or hate them. Working through both of his books, Running: Biomechanics and Exercise Physiology Applied in Practice (coauthored with Ronald Klomp) and Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach, was a challenging process for a math teacher like myself because I do not have a background in anatomy and physiology. I am thankful that I did because it opened my eyes to many new areas I did not consider in the past, and most importantly, they made me think.

A big part of Bosch’s work is addressing transfer. “Strength training is coordination against resistance,” defines the purpose of Bosch’s second book. I never looked at strength training through this lense before. I viewed strength and coordination as two separate entities, but assumed that improvement in one would lead to improvement in the other (a stronger athlete would create a faster athlete). The correlation between strength and speed (which is dependent on the bodies ability to coordinate expression of force) may be strong with many high school athletes, but my experience in coaching has shown that it is not absolute. Viewing strength and coordination as a tandem is powerful. In simple terms, strength is pointless unless the organism has the coordination to express it in sport-specific movements. Bosch gives the following situation which is worth consideration for anyone who works with athletes in sports where single-leg support occurs:

“One example is the frequent use of a double-leg squat with barbell weights to improve single-leg contextual movements such as running and jumping on one leg. It is simply taken for granted that there will be transfer – but in reality this is not the case. In fact, it is easy to explain why transfer does not automatically occur. There is an important difference in coordination between the two movement patterns, and this may well be controlled quite differently by the central nervous system. A single-leg toe-off involves not only knee and hip extension but also abduction in the hip (so that the free/swing side of the pelvis is elevated during toe-off). This abduction requires a great deal of strength and does not occur in a double-leg toe-off.”

Bosch refers to the elevated pelvis in a single-leg toe-off as the “hip lock” position. You may be familiar with the sprinter below showcasing the position. The pink line demonstrates how the portion of the pelvis on the side of the swing leg is elevated.

Here is a link to an image from Bosch’s book showcasing the position. It also applies in multi-directional sports. This guy was pretty good at getting there.

Getting into the hip lock position IS NOT automatic. In this video, Dr. Shawn Allen of The Gait Guys discusses the cross-over gait. It is clear that an athlete with this issue will not have a higher swing leg hip.

So what can be done to enhance the ability to get into the hip lock position? Below are some videos that show some possibilities (note – hip lock is not the only concept addressed in these exercises).

Tap to hip lock exercise:

Aqua bag balance to diagonal snatch:

Sample drills from Japan Rugby (who Bosch has worked with):

More content from Japan Rugby:

Sample drills/exercises from a Frans Bosch Seminar promotion:

Boom complex via Indiana State (and former Minooka) athlete Justin Wolz:

**** For those interested in the boom complex, Chris Korfist has a 12-week progression for sale here ****

You will notice that within these videos the intention of many of the movements is similar, but there is quite a bit of variation. Arm placement/movement, trunk rotation, as well as varying rhythm, implements, and surface are all used to create a more robust athlete. It is impossible to account for every situation an athlete will encounter in competition, but by picking out primary movement intentions and progressively working the athlete through variations, the athlete’s bandwidth in performing the movement becomes wider. They will be able to deal with imperfect situations more effectively.

A concept worth consideration in Bosch’s methods is reflex training. Movements such as running and single leg jumping involve the stumble reflex (e.g. stance leg shoots forward when the swing leg gets caught on an object) and the crossed extensor reflex (e.g. swing leg shoots down when the stance leg steps on something sharp). In the aqua bag balance to diagonal snatch video, the stumble reflex is used initially when the swing leg moves forward and the stance leg pushes back. The crossed extensor reflex is used when the swing leg is driven up to the box and the stance leg is exerting force down into the ground. Bosch’s argument is that since the exercise (aqua bag snatch) is specific to the activity (sprinting), more transfer will occur.

This in no way encompasses all of the content in Bosch’s two books. His ideas may seem radical to many, but many are movements that can be incorporated into warm-ups, workouts, and weight sessions fairly easily. I think all track and field and cross country coaches would benefit from reading both books (he also has a DVD: Running – The BK Method). Coaches of other sports should prioritize Strength Training and Coordination.

The Triphasic Methods of Cal Dietz

I read Cal Dietz and Ben Peterson’s Triphasic Training a year and a half ago and it was tremendous. Dietz and Peterson did a terrific job of taking complicated concepts and breaking them down to a simpler form…..ideal for me because I’m not very smart. Since then I have read pieces of Dietz and Matt Van Dyke’s version tailored to high school athletes, Dietz and Chris Korfist’s version tailored to high school football, and I will be working my way through Matt Van Dyke and Dietz’s version tailored to lacrosse in the near future.

Some of my favorite content within the original book were the examples that showcased how triphasic training came to be, or how it had an effective impact. Before those are discussed, however, here is a brief description of the methodology:

- Dynamic movements require muscles to undergo eccentric, isometric, and concentric contractions

- Eccentric – Muscle lengthening and absorbing energy

- The ability of the muscle to handle force while decelerating

- Isometric – The link from eccentric to concentric

- The ability to transfer the eccentric movement into a concentric movement instantly

- Concentric – Muscle shortening and expelling energy

- The ability to handle force while accelerating

- Eccentric – Muscle lengthening and absorbing energy

- A weak link in any of the 3 contractions limits force production

- Training all 3 phases in a block format will allow the athlete to decelerate and accelerate faster

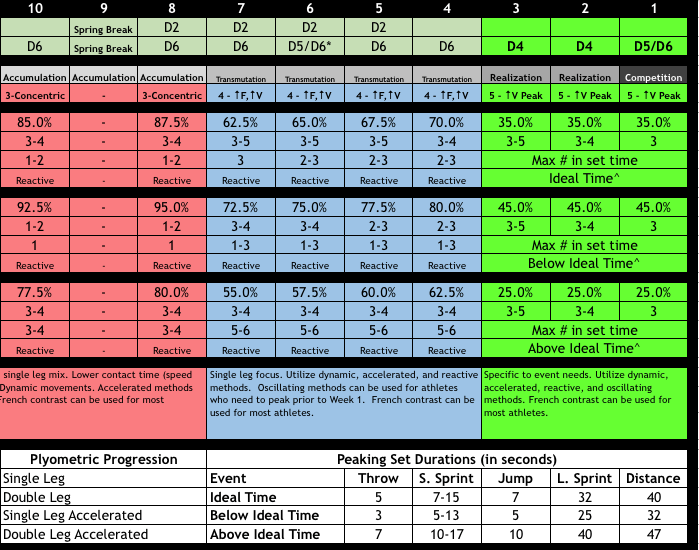

The best part of the triphasic method is that it can be easily implemented. After a few weeks of establishing general strength, 2 – 3 weeks a piece can be spent focusing on training the eccentric, isometric, and concentric phases. Below is a tentative progression we plan to work our way through this upcoming season:

Here are links to videos of the variation in the lifts specific to the phase being addressed. The general concepts can be applied to most lifts.

- Back Squat

I think one reason why Cal is well respected in the world of physical preparation is he is extremely humble. I have heard him say that when he is with a group of people, he assumes he is the dumbest person in the room. It allows him to always be in a growth mindset. A second reason is his methods have been developed from extensive athlete testing. He has had access to equipment like force plates and an Omega Wave system, which gives validity to his findings.

One of my favorite examples given that relates to the idea of transfer has to do with baseball players being tested in the pro-agility test (5-10-5). At the beginning of the year, the players were tested in the drill. They were then divided up into two equal groups. One group was trained in a “traditional” training program which included normal lifting (concentric focus) and practicing the drill three times per week. The second group focused on eccentric and isometric (triphasic) training, and DID NOT practice the drill at all. At the end of four weeks the athletes were retested. The traditional group improved their times by 2%. The triphasic group improved their times by 8%! A few takeaways from this example and triphasic training in general:

- Training athletes using triphasic improves their ability to change direction. This is a great selling point for track coaches who implement triphasic when they have to deal with the argument of linear speed being different than multidirectional speed.

- Dietz used standard exercises with the triphasic group, but made them unique by varying the tempo. Specifically used were “slow tempo eccentric squats and single leg isometric deadlifts to make the hip extensors as strong as possible to be able to absorb force at high velocities going into the turns of the pro-agility test.” To me, those movments seem less specific to the task than some of the Bosch exercises, yet they clearly had transfer.

- One aspect that I love about triphasic is the methodology lends itself to teaching lifts extremely well. The slow descending tempo of the eccentric focus gives the coach the opportunity to help correct improper movement and athlete to wire in the ideal “descent.” The isometric tempo has a maximum controllable descent followed by achieving perfect position at the “bottom” of the lift. The concentric tempo puts it all together.

There is so much more phenomenal material in the triphasic books. Simple explanations of anatomy and physiology, RPR (reflexive performance reset), ankle rocker, French contrast, glute layering model, and numerous stories and explanations of why the methods have been successful are just some that come to mind. These books are must reads for anyone interested in physical preparation.

The Speed Focused Methods of Derek Hansen

I have never seen Derek Hansen speak, but I have listened to every podcast he has been a part of that I could find and I have read many of his articles. I enjoy his work because I think he is extremely practical. One of my favorite works of his is, “Sprint Training: The Complete System.” The basis of it can be summed up in this quote from Hansen,

“I tell all that will listen to build their training programs on a foundation of speed.”

Movement connects all sports. Generally speaking, being able to move at a higher speed is better, so doesn’t it make sense to make this the primary focus and build everything else around it? I understand that size and strength are prioritized more in certain sports, but even within those sports, the bigger and strongest athletes which have the most speed are the most sought after.

It drives me crazy how overlooked of an exercise sprinting is. Does anything else put a force of five times body weight into the ground in under .09 seconds? Yet we try and consistently come up with other ways to improve sprinting besides sprinting. In a presentation given at ALTIS, Arizona Cardinals head strength and conditioning coach Buddy Morris stated,

“Sprinting drives up your weights. Weights don’t necessarily drive up your sprinting.”

I would even argue that this would be true in submaximal sprinting where developing rhythm and flow are the focus. If all else had to be taken away, sprinting gives you the most bang for your buck. However, many programs hide in the weightroom in the offseason, neglecting max and submax sprinting, which is THE primary movement in sport. Hansen states:

“For some reason, it is hard for many people to understand why sprinting is such an important cornerstone of a complete training program. Just like sleep and drinking water, many people do not sprint enough (or in many cases – they do not sprint at all) and find that their performance and resiliency suffers as a result. The excuses for not sprinting are weak at best. In most cases – like numerous simple tasks – people have no knowledge on how to implement a sound sprinting program. Others worry that they may get hurt doing sprint training on a regular basis.”

It isn’t very hard to create a sound sprinting program. Start with short maximal runs (5-10 m) and gradually work your way up to distances where athletes achieve maximum velocity. For high school athletes, this could be anywhere from 15 to 50 meters. Give full rest between reps. Timing using a system such as Freelap to get maximal effort is ideal but a stopwatch works if you are on a budget.

The following day focus on submaximal work addressing rhythm and flow. I’m fond of short hurdle runs (wickets) followed by a sport-specific workout. I would emphasize addressing movement in all three planes on day two. Rest the third day and repeat, maybe with the addition of a total body circuit on day six. It can be that simple simple of a structure. Coaching effectively within the structure is not so simple, but that is beyond the scope of this article.

Another topic I think is commonly misunderstood by team sport coaches (and some track coaches) is training maximum velocity. The only way to train true maximum velocity is when athletes are fresh. I think that many team sport coaches feel their athletes are not 100% fresh during competition, so their true maximum velocity may not be reached, and therefore they do not see the benefit in training it. I think this logic is flawed because if athletes train at their true maximum velocity, their nervous system is not shocked when attaining speeds at or near it during competition. A shocked nervous system can lead to injury. Dr. Ken Clark recently stated in the Building Better Athletes Podcast that field sport athletes are above 90% of top end speed a large percentage of the time because they reach that level 10 to 15 yards into a linear sprint. Training at 100% of top end speed will make 90% more manageable for the nervous system. Furthermore, “game-breaking” plays often occur when athletes are moving at or near maximal speeds. Team sport coaches typically pride themselves on preparation. To me it makes sense to ensure athletes are prepared to deal with maximum velocity by training it properly.

But how does linear speed tie into the change of direction needed in team sports? Hansen addresses this by saying,

“Even more laughable are the people that claim linear sprinting is not useful or ‘functional’ for team sports because of the agility requirements of these sports. People – watch a goddamn sporting event! Guess what? Athletes, more often than not, sprint in straight lines whether it is soccer, basketball, football, rugby or baseball. Given that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, I would say that sprinting linearly would be a good strategy.”

Hansen also feels that if he can improve an athlete’s linear speed, it will transfer to the ability to change direction because improvement in linear speed requires increase in strength, power, and elastic performance abilities. In regards to deceleration, he notes that every time an athlete performs a sprint, he or she decelerates gradually which provides a safe eccentric challenge for the athlete. That accumulation creates competence in deceleration. Like Dietz, he has seen improvement in agility test results when no formal agility training has been present (2016).

I would highly recommend investing time into the information that Hansen has put out (articles, podcasts, etc.) It is my understanding that he plans to release a book in the near future as well. I am eagerly awaiting its arrival!

Putting It All Together

I am far beyond thinking it is necessary to have all of the answers, but that does not mean I intend to stop looking for as many as possible. Some of the ideas discussed mesh well together…..others conflict each other. The trick as a coach is to determine what works for your unique situation. What may work for your program now may not work in the future. The converse of this may also be true. The following are a set of principles I think any training program should take into account.

- As Hansen said, make speed the centerpiece of your program and build everything else around it. Programs that expect optimal speed improvement by only doing work in the weightroom is equivalent to baking a chicken and expecting it to taste fried.

- We should always look for ways to address the individual needs of our athletes. This article gives an introduction into many different exercises and methods. There are an infinite number of others out there. Obtain as many tools as possible! Cookie cutter programs are okay, as long as the cookie cutter has contingencies and can adapt to the needs of each individual athlete.

- To extend upon the concept of individualization, NEVER underestimate the power of athlete preference in training. Athletes who like what they are doing, or feel like what they are doing will benefit them, will have better training sessions and better results. Here are some examples:

- At the second Track and Football Consortium, Dietz said he once trained identical twins with very similar ability. They were given the same workout. One of the twins loved the workout, the other hated it. The twin who loved it had a better workout and a better response from it via testing.

- At the fourth Track and Football Consortium, Stuart McMillan (sprint coach at ALTIS) showed how he uses a 2×2 matrix to categorize the types of lifts his athletes will perform. The rows of the matrix are single and double, the columns are push and pull. Part of the method he uses to determine where an athlete will fall is pretty complex…..he asks them what they would prefer to do. For example, he would ask if an athlete would prefer to squat (push) or deadlift (pull). Then single leg or double leg would be addressed. McMillan’s (and other phenomenal) presentations can be purchased here.

- Here is an article that discusses the power of exercise and belief – Believe it or not: Exercise does more good if you believe it will.

My search for transfer will always be ongoing. I hope I look back at this article 5 years from now and question some of the ideas. It will mean I have not remained stagnant. I hope you have found something that assists you in finding the supermen and superwomen that are within all of your athletes!

Feel free to contact me directly at rassise@hf233.org.

References

Bosch, Frans. Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach. 2010 Publishers. 2015.

Clark, Ken. “Episode 12 – Dr. Ken Clark: Speed Science.” BBA Elite Performance Podcast. 26 Dec. 2016.

Dietz, Cal and Peterson, Ben. Triphasic Training. Bye Dietz Sport Enterprise. 2012.

Dietz, Cal. “The Magic of the French Contrast.” Track and Football Consortium 2. 12 Dec. 2015.

Hansen, Derek M. “Sprint Training: The Complete System.” Strength Power Speed. 10 Aug. 2016.

Keagle, William. “Introduction to the Modern World.” Millikin University. Aug. 1999.

McMillan, Stuart. “Developmental Progression for the Strength Training of Sprinters and Football Players: A Reverse-Engineering process.” Track and Football Consortium 4. 3 Dec. 2016.

Morris, Buddy (via @StuartMcMillan1). “Sprinting drives up your weights. Weights don’t necessarily drive up your sprinting.” 3:54 p.m. – 11 Nov. 2016.

Comments 10

Dr. Keagle! Changed my major as a result of my first class in college with him!

Love the AQUA BAG BALANCE TO DIAGONAL SNATCH. We do something similar for our pole vaulters!

Great stuff Rob. Almost wish I was a sprinting coach!

Patrick Sheridan

Author

Patrick,

Great to hear from you! Dr. Keagle was able to get a math major out of bed for an 8 a.m. class 3 days a week. A testament to his greatness. Vaulters are sprinters too! Thanks for reading!

Outstanding, Rob!

Author

Thanks for reading John!

Great, great article! Love the videos. Lots of great ideas in all this to help runners of all distances…

Andy,

Thank you for reading! I completely agree that the work of the coaches discussed is applicable to all runners….along with athletes in other sports!

Rob I have read your articles with much interest. I am both a high school coach and a USATF certified coach. I have studied Bosch and Hay as well as looked at the some of the new things proposed by Holler and Korfist. Much of it is a rewrite of Level 2 and 3 teaching of USATF as taught by Winkler, Seagrave Schexneyder, et at all. The names have been changed but the material is still there. I was last part of a Level 3 in the 90s

Author

Hi Patrice,

Thank you for reading and your input!

I can only speak for myself in saying that my ever evolving philosophy is based on the genius of others (such as the men you mentioned…I just saw Boo speak for 6 hrs this weekend!) and my own unique experience.

I don’t know the true origination of many of the concepts we use. I think most come from experience, then get passed down/around, and then science verifies them.

I’m not sure if there are any original methods out there, but when someone develops a method based on what he/she has seen from athletes (not learned from an outside source) the idea is original…even if the method has been around for 100 years.

There are so many ways to obtain information these days. My personal goal is to find quality information that may challenge my beliefs, have an open mind, and be focused on progress.

What were the biggest take-aways for you in your level 2 and 3 training?

Great article with fantastic resources.

I’ve followed a somewhat similar path as you…finding Holler and Korfist and then reading deeper into their influences with Bosch, Dietz, etc.

I wanted to add to your final section, in particular about athletes “enjoying” or having “belief” in a workout.

This is the first year in which I’ve abandoned all traditional speed drills. Instead we’ve been using the progressions from Korfist (booms, toe/ankle, hips) plus the mini-hurdles and breathing exercises (including some RPR, Dr. Tom Nelson’s core work and nasal breathing only during drills.)

What is interesting is that the kids are more focused on the drills. No more lazy A-skips or terrible carioca. They seem to concentrate and therefore participate more actively in the drills. By changing the drill slightly every week, they are presented with a new challenge. Obviously like Bosch’s books we know the physical reasons why this is good. But the kids themselves like the challenge. It makes it fun. We’ve even done “Toe Pop Chasers” where they race doing toe pops.

When they see progressions, they know they are getting better or improving each week/workout. This adds to “believing in the workout”. When you add the “push-pull” or “halos” to the booms they have fun figuring out that challenge. As an example, we did the “Hurdle Skips”. It was great watching them figuring out how to do it and then seeing the confidence of figuring out and going through a bit faster or with more rhythm and better posture.

Adding a weightlifting component since I’ve gone to Alton has been a thorn in my side (the weight room is very far away from the track plus they do not get out of school until 3:15).

I am really interested to see how your plan goes with Triphasic/French Contrast training and I hope you write a follow-up on it in May (or possible end of indoor) about your results, especially the length of the sessions, learning curve, etc.

Jeff,

Thank you for reading and sharing! For years we have been altering warm-ups to make them less monotonous. We have made progress, but we have still ended up in the situation where athletes are going through the motions. After reading Bosch and hearing Korfist speak at TFC 4, Nate Beebe (head coach at HF) and I sat down and went through progressions of movements we wanted to include. We are pretty excited about the physical set-up we will be using for the warm-up along with the progressions. Our plan is to have our leaders learn and teach the progressions while we can go through daily movement assessments to see how our athletes are feeling. It’s great to hear that your athletes have enjoyed your new structure! I imagine this will begin to become the new norm….much like dynamic warm-ups did 15ish years ago.

In regards to triphasic, we used it last year and I think our athletes really enjoyed (and benefitted) from it. As I mentioned in the article, the eccentric and isometric phases are ideal for teaching proper positions. Another perk is it is “Bosch-like” in terms of keeping the athletes interested. We do pretty similar movements throughout the year, but the way in which we do them changes. All of our guys LOVE the French Contrast (probably because of the assisted band jumps). There’s no question that some of our best WR workouts consisted of a French Contrast because of the enthusiasm our athletes had for it.

I hope to continue to add to my “search of transfer” in the future. Thanks again for your response!